Far Beyond the Walls Exhibition Essay

SURVIVING THE CLOCK WITH NO HANDS

He didn’t speak to me of evil

But the man showed me hell

When he said, “The excluded still wait….”[1]

From my own limited perspective and talks with formerly incarcerated people I have met and read about, there appear to be 3 options once imprisoned: fail to thrive, languish, and self-destruct, or become a super-human, bigger, stronger, faster more terrifying and unapproachable, able to endure anything like an invincible mountain, …and/or find ART.

I would like to focus on the third option…. find art.

Jumping back in time to contextualize, it is important to note that when public torture and the gorey spectacle of punishment disappeared from Europe and America in the late 1700’s, it was supplanted by imprisonment, when the convicted person became completely invisible to the public. Their ability to choose, move, have options and individuality all removed. In effect erased. Out of sight out of mind.

To the legal system and the State, the safety of the public was of primary concern, the rehabilitation of the convicted was not. It is because of this lack of foresight, research, and humane planning that recidivism is extremely likely. Once you have been imprisoned the probability of returning behind bars is very high. According to data from the Bureau of Justice Statistics, 70% of prisoners released in 2012 were arrested again within five years, The recidivism rate is over 80% for prisoners with juvenile records.[2]

The experience of time in prison is expressed by the street phrase “a clock with no hands” meaning doing time, a long, long time. It refers to prison temporality…. Clocks …symbolize an unrelenting aspect of penal time: the waiting.[3] Finding a way to mark time, survive mentally, emotionally, physically, and spiritually has been left to each inmate without many, if any resources allocated to them. Inmates that found an art practice while inside seem to have overcome some of the immense difficulties that materialize while being systematically dehumanized, confined, restricted, and controlled within the carceral complex. Outstanding New York based artist Jared Owens used art as a way of “recalibrating his sense of time” ….it was a tool to manage penal time by using his imprisonment as a vehicle for creative expression…”[4] He used soil from the prison grounds in his paintings …turning it into art matter.[5]

I visited Owens’ studio in NYC in 2022, when he was a recipient of the Silver Arts Project Fellowship.[6] The award was a year with the most incredible studio space in the new One World Trade Center. The monumental spaces had floor to ceiling windows with astounding views over New York City. The work that most resonated with me were his lino-cut prints. Repeated motifs of black and brown figures standing in stacked lines across the canvas substrate, referring perhaps to the scratched tallies of days on prison walls, but also to queues and line ups with inmates leaning, slouching, standing maybe socializing while on their limited outdoor yard time.

Owen’s work was presented in an impressive exhibition in NYC in 2022 by Dr Nicole Fleetwood, an advocate, academic, writer and the curator of Marking Time in the Age of Incarceration, an empathic and brilliantly researched book, and a physical exhibition of incarcerated and formerly incarcerated artists, at MOMA PSI in New York City in 2020. She states: Prison art practices resist the isolation, exploitation and dehumanization of carceral facilities. They reconstitute what productivity and labor mean in states of captivity…[7] Prison art is part of the long history of captive people envisioning freedom-creating art, imagining worlds, and finding ways to resist and survive.[8]

While researching for Far Beyond the Walls exhibition I came across this concept of imaginary worlds many times. UK based artist Kevin Barron used collage techniques, creating impossible worlds to endure and bridge his time while incarcerated. The effects of the artwork benefited his own psychological health during his time inside, making images on which to imagine and dream. Barron was fortunate as the prison he was housed in had a few, very limited art supplies available, and allowed him to create these collages[i] in his cell openly with his prison issued razor, cardboard and glue.

[i]A Picture is a Poem Without Words. Collage 12, Kevin Barron. Magazine images collaged on cardboard substrate.

Many prisons do not have art programming, or (I read), withhold it as another control mechanism, and those inmates that need to “make” or “create” must be ingenious, and self-disciplined, they must find new ways to manage penal time, obscure any visible artmaking activities and become enmeshed in the circulation of prison currencies. This internal economy leads to procurement of materials, which can take many forms.

Currency can be obtained through performing services, Teddy (Catfish) related to me that he was OJ Simpson’s pedicurist…and that OJ owed him over $4000. Currency is also trade based, someone has access to sheets such as were used in acclaimed artist Jesse Krimes’ work,[9] someone else has access to paper or cardboard boxes and maybe someone else has extra soap or toothpaste. Fleetwood relates to the community building developed through this prison economy, writing that artists acquire state property to make art; and of how getting possession of material is based on relationships among incarcerated people; and how both art-making and the friendships that art can facilitate refuse the punitive codes, social isolation, and racial divisions that govern prison life.[10]

One of the positive attributes of being an artist in prison is that the art itself becomes currency. Portraiture is highly sought after. Placing the subject in a situation of their choosing, giving them a visual image, their own visibility, an identity other than the number assigned by the state. It is of deep importance to retain or regain individuality, portraiture helps to build this alternative survival narrative. Something to hold on to and build upon.

One of the terms used in prison for art and prisoner made objects is mushfake, Fleetwood’s definition is: MUSHFAKE – DIY creation of versions of objects that could be found outside of prison, made from penal matter.[11] “Mushfake may involve months of creative planning and organizing to acquire material or state goods…..Incarcerated artists redefine the term “procurement” to refer to prisoners’ unauthorized acquisition of state goods for art making, survival and challenging prison authority.”[12]

It is not only the deep focus required for making art and building a serious art practice but the time, thought, effort, and work-arounds needed to be able to even commence a project. Planning could take months. Evidence of mushfake ingenuity and creativity can be seen in the helicopter[iii] built by inmates of the Nevada State Prison in the 1970’s.[13] The sheer determination, collaboration, and assistance of other inmates to make and hide such a huge item for an escape plan, is an inspired and amazing example of collective spirit and community building.

[ii] Helicopter built from reclaimed and procured materials by inmates of the Nevada State Prison 1982.

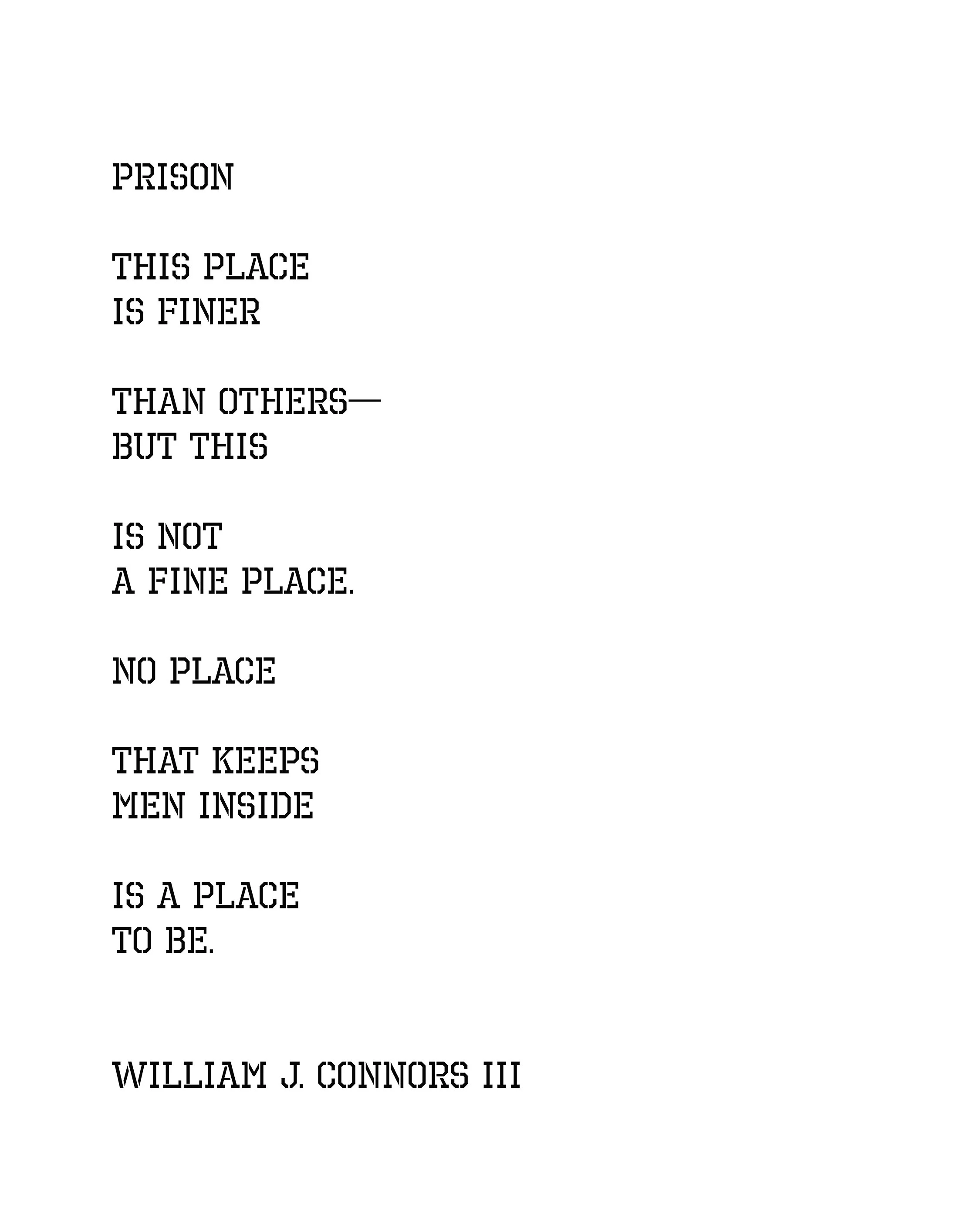

Poet William J Connors III, who was incarcerated for 22 years in Nevada’s prison system told me that finding poetry changed his life. He related to me that he was living in a concrete box with a small window, but that the world outside was obscured. He couldn’t see through the glass, sensory deprivation was extreme. Poetry and the lessons with Nevada’s Poet Laureate Shaun Griffin changed everything. He could go anywhere with his mind through creative use of language and dreams. Connors spoke of how wonderful life is, and how writing hundreds of poems, some of which were posted on Reddit by a friend, gave him feedback and a lifeline to the outside world. Tiny threads of humanity reattaching him to the potential for a normal life full of choices and travel and family and friends. Prison is one of his poems written during his incarceration.

William J. Connors III [14]

In the foreward of Razorwire XVI Shaun Griffin gives us a perspective and insight into the art program he volunteered on, teaching poetry to inmates for more than 30 years at Nevada Correctional Center.

Somehow the workshop persists. Against an expectation of silence, the men find a way to create, to keep some part themselves on the page, whether as poetry or painting, they manage the ebb and flow of art inside. I have given up trying to explain why this is so; we meet every other week in the chapel and begin. There are no qualifications, no reason to participate except its lasting presence. Which, on the yard, defies explanation because to be saved is not spoken about. Outside of religion, there is no saving to be had. It is mostly seen as a curiosity. Of necessity, it has become thread to a larger universe of poets, novelists, essayists, journalists, painters, and others who vouch for art as viscera in the cold inertia of prison.[15]

Far Beyond the Walls exhibition aims to expose the general public to carceral spaces and open channels for dialog, offering artists’ insights from the outside and from incarcerated and formerly incarcerated artists inside our communities via poetry and visual art.

Art is another form of communication when words aren’t available. The idea that art can save lives by constructing an identity, a foundation, and tools for each individual to process their lives, trauma, emotions and as a vehicle for self-expression, is a powerful one. Art and creative thought can give inmates a new lens with which to view the world, alternative ways to create relationality and kinship while augmenting the hope and will to succeed in a productive and healthy life while behind bars and on returning from captivity to the outside world.

Art’s great power lies – in its capacity to make us see things in a different way, make us perceive new possibilities.[16]

Essay by

Frances Melhop MFA

Artist + curator + gallery director

FOOTNOTES

[1] Excerpt from poem by John Fenton. Lukewarmed Fenton, John. Edited by Shaun T Griffin. Razor Wire XVI 16 (2018).

[2] Author(s) Matthew R. Durose. “Recidivism of Prisoners Released in 34 States in 2012: A 5-Year Follow-up Period (2012–2017).” Bureau of Justice Statistics. Accessed May 15, 2024. https://bjs.ojp.gov/library/publications/recidivism-prisoners-released-34-states-2012-5-year-follow-period-2012-2017.

[3] P41, Fleetwood, Nicole R. Marking time: Art in the age of mass incarceration. Harvard University Press, 2020.

[4] P82, Fleetwood, Nicole R. Marking time: Art in the age of mass incarceration. Harvard University Press, 2020.

[5] P 85, Fleetwood, Nicole R. Marking time: Art in the age of mass incarceration. Harvard University Press, 2020.

[6] Jared Owens - Overview | silver art projects, accessed May 16, 2024, https://www.silverart.org/artists/47-jared-owens/overview/.

[7] Introduction P3, Fleetwood, Nicole R. Marking time: Art in the age of mass incarceration. Harvard University Press, 2020.

[8] Introduction P6, Fleetwood, Nicole R. Marking time: Art in the age of mass incarceration. Harvard University Press, 2020.

[9] “Jesse Krimes.” jessekrimes. Accessed May 15, 2024. https://www.jessekrimes.com/.

Krimes series Apokaluptein:16389067 was conceived and executed within federal prison. The title references the Greek origin of the word apocalypse meaning to ‘uncover, reveal;' an event involving destruction or damage on a catastrophic scale; the numbers reference Krimes' Federal Bureau of Prisons identification number. He smuggled the contraband works through the Federal Bureau of Prisons and the United States Postal Service, piece by piece, over a period of three years, resulting in a forced Exquisite Corpse with himself. The resulting work is a series of 39 disembodied prison sheets sutured together, making up a collective installation as vast as the history and timeline represented over his seventy-month absence. Krimes developed a hand-printing procees, using hair gel and a plastic spoon to transfer the images he collected from The New York Times onto the surface of the sheets. The fragmented images, removed from narrative sources are inverted and effaced from their supports. Through hand-drawn alterations, he unified the disconnected images into new visual narratives.

“Apokaluptein:16389067 (2010-13).” jessekrimes. Accessed May 15, 2024. https://www.jessekrimes.com/apokaluptein16389067.

[10] P57, Fleetwood, Nicole R. Marking time: Art in the age of mass incarceration. Harvard University Press, 2020.

[11] P63, Fleetwood, Nicole R. Marking time: Art in the age of mass incarceration. Harvard University Press, 2020.

[12] P65, Fleetwood, Nicole R. Marking time: Art in the age of mass incarceration. Harvard University Press, 2020.

[13] I am told the helicopter was built in the 1970’s by inmates and returned soldiers, veterans of the Vietnam War convicted of crimes and housed at the prison. It was confiscated and destroyed. The photograph is the only recorded momento of this remarkable collaborative effort.

[14] Connors, William J. Edited by Shaun T Griffin. Razor Wire XVI 16 (2018).

[15] Foreward by Griffin, Shaun T, ed. Razor Wire XVI 16 (2018).

[16] Mouffe, Chantal, Elke Wagner, and Chantal Mouffe. Agonistics: Thinking the world politically. London: Verso, 2013.